On organizational structures — the QRF team model to crush interruptions

Take control of engineering team interruptions and prevent them from happening ever again.

As an engineering leader, I’ve found many products and engineering teams at startups struggle with being agile.

The shortcuts the startup took early on getting to the point where they could grow had benefits, but also costs. At some point, enough technical, capability, knowledge, and organizational debt has been created such that there is a constant stream of bugs, internal asks, interruptions that only the engineering team can handle.

These ask come in at a rapid pace, sometimes several days, greatly disrupting the work of an engineer. Even if each interruption only takes a few minutes, the context switch alone can destroy any hope of productivity for that afternoon.

How can an organization handle these in a way that makes sense?

Enter the QRF Team

The QRF model works incredibly well in certain contexts without the negative drawbacks of other approaches.

What is it?

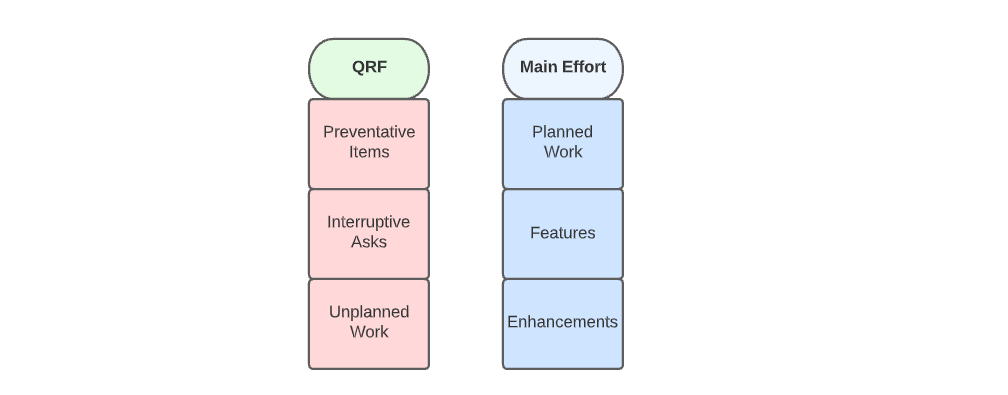

You split your engineering organizational unit into two discrete, independent teams:

Team 1, designated as the Main Effort

Team 2, designated as the QRF

Team 1’s charter is simple: build what’s on the roadmap. They act as a typical product development team does, working on high-value, high-priority items at a road mapped, predictable tempo, using whatever framework or methodology is appropriate — eg. Scrum or Kanban.

In short — they work on the main effort of the company.

Team 2’s mission is to tackle any item that would cause an interruption to Team 1. They act as the QRF, the Quick Reaction Force, to jump in front of any problems that would otherwise interrupt the sprint. In short — they prevent interruptions and act as a supporting effort.

QRF solves problems found in other approaches

The reason QRF works is that the other commonly adopted “agile” approaches have fundamental drawbacks that limit their effectiveness in certain cases.

These approaches include:

Working only on the valuable items

Putting it in the next sprint

Setting aside a set capacity/timebox per sprint

Why working only on valuable items fails

What will win a prioritization argument:

Setting up a user account

An idea that can generate $1,000,000,000

The next billion-dollar idea will always win any prioritization argument, because it’s an unknown, idealized, easily manipulated projection. However, focusing exclusively on innovating with new product ideas means your current customers are not being served.

This is the delta between innovation and operation: you need both to thrive in the market, but most product prioritization arguments devalue operations. Few product managers want to work on an incrementally valuable item when the option is an exponentially valuable one.

This means the incremental things: internal tooling, bug fixes, automation, tech debt, etc. all fail to be prioritized when viewed exclusively from the lens of “value”. This is because they often have some known, smaller quantifiable value, and these pale in comparison to the idealized unverified projections.

At the end of the day, prioritization is an art, not a science, no matter how many structured frameworks we use.

Why putting it in the next sprint fails

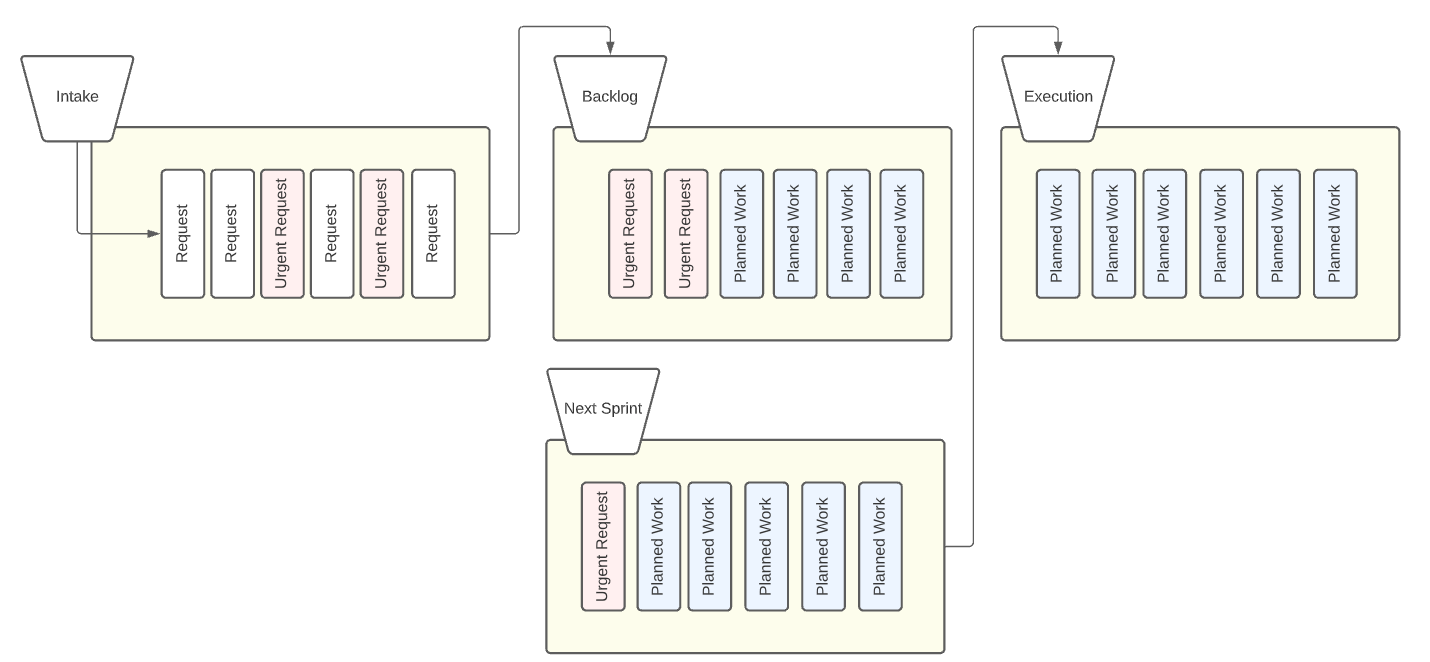

Some teams try to solve this problem by sticking rigidly to the sprint commitment. Whenever an interruption request comes in, they say “we’ve already planned this sprint, so we’ll put it in the next sprint”.

Unfortunately, by the time the next sprint comes along, there’s an additional 15 items in the backlog, all needing to get done.

Rinse and repeat until there’s a large list of items, most of which never end up being completed. The team starts being viewed as inflexible by customers, others in the company, and by executive sponsors.

Why does this approach fail?

The approach assumes that things can wait until the sprint is over.

The truth is, some things can’t wait. Compliance demands, a new employee onboarding, a large customer’s tiny configuration change — these are activity-generated work that just needs to get done with some sort of time-sensitive cadence.

Not fulfilling these requests within a short amount of time can cause reputation damage or operational risks.

Why setting aside set capacity fails

Another approach teams take is to dedicate a certain amount of time, such as 10% of a sprint, or a single day a week, to solve these issues.

Why does this approach fail?

For low-volume interruptions, it works, but for organizations with a high volume of interruptions, it doesn’t — the rate of intake just gets too overwhelming.

Additionally, by making it a “10%” thing, it causes a belief that the work is unimportant and a distraction. This means engineers aren’t as motivated to complete it, which results in a certain level of ineffectiveness when executing on these tasks.

There’s also an implicit assumption that you can actually get enough of the items done within that time-box.

In many circumstances, you won’t, and then you’re back at square one.

Let’s solve the real problem

The real problem here is that the team is operating at a tempo that is slower than the environment demands.

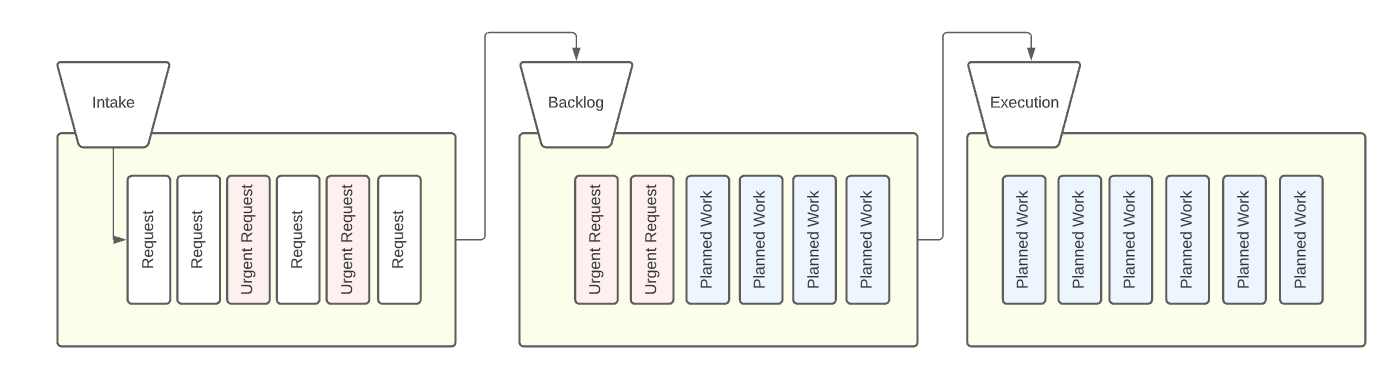

If you get five urgent requests every day, but you only pick up new work every 2 weeks, that means customers can potentially wait up to 4 weeks just to get something resolved. In the startup world, 4 weeks can be an unacceptably long time. That assumes it manages to find prioritization against the planned roadmap (which is often not the case).

This ultimately causes things to pile up, customers to get unhappy: “why does it take a week to set up a single configuration?” Perception is impacted negatively.

This is why the QRF solution works well — it forces an operation at a faster tempo.

There are a lot of other benefits with the QRF model

Systematic reduction of context switches

The first and foremost benefit is that interruptive tasks can be handled by a single, dedicated execution stream. While that team may context switch frequently, the organization as a whole ends up switching away from important things less.

This helps prevent context shifts away from the primary focus of the organization, which should be on non-urgent, important work.

It’s ultimately a system-level optimization at a local-level cost.

Improved organizational agility and responsiveness

A second benefit is that it increases the organizations’ perceived responsiveness to requests.

Many organizations will perform some form of agile ritual where direction is pivoted and work is defined and set every 2 weeks. This means, in an unlucky case, there’s a theoretically maximum lead time of up to 4 weeks from the point a customer makes a request to the point it is fulfilled.

The QRF team helps provide a faster response time for such requests. I’ve seen consistent lead times of under 3 days from request to delivery for items — it helps improve customer satisfaction and service satisfaction.

Dedication to maintenance and support

Maintenance is the most costly aspect of a system’s lifecycle. It gets costly because it often gets delayed, which increases the risk and work required to maintain the system.

The QRF helps ensure that important maintenance doesn’t go undone — eg. things like bugs, operational tooling, and other items.

How QRF Operates — in more detail

Operating Modes

QRFs operate with two operating modes:

Reaction

Standby

During “Reaction”, the QRF team is actively firefighting — solving some urgent, interruptive issue as the first line of defense against interruptions and supporting the other team by allowing it to focus.

During “Standby” the QRF team works on preventative “shift left” items or things that help it react faster. These could be internal tools, improved monitoring / alerting, quality-of-life improvements, automation, or improved observability in logs or audits — it’s up to the QRF team to decide how they want to fill this time.

Shift Left

The biggest part of QRF’s mission is to “shift left” on interruptions. They should strive not just to react to solve the instance of a problem but to avoid the entire class of problems from ever reaching engineering in the first place.

What does shifting left look like on QRF?

This looks different for every company and problem, but some common “shift left” solutions include:

Creating admin tooling to let internal teams perform actions on their own

Fixing bugs or UX in areas of the product that lead to engineering requests

Improving monitoring, traceability, and observability so that investigations can be completed faster

Creating easy-to-use queries or exports so others can see data they need without engineering

Documenting common engineering maintenance tasks so that others can solve it

Over time, as categories of interruptions are shifted left, the engineering organization as a whole has more room to focus on the execution of higher-value items.

Working with stakeholders

QRF works closely with stakeholders across the entire organization — especially internal teams like support, customer success, and operations. It’s important to stay in touch with these stakeholders and keep them consulted or informed regarding any changes to their workflows or resolutions to requests they may have made.

Measuring QRF Performance

There are several ways you can measure how a QRF team is performing:

Issue Resolution Rate — how many issues did the QRF team solve?

Cycle Time and Lead Time — how long did a requestor wait for “done”?

Items Shifted Left — how many issue types and issues did QRF prevent?

Interruptions Prevented — how many urgent items did the main effort team not have to handle?

All of these are legitimate ways of evaluating that the QRF is working.

Issue Resolution Rate is essentially the throughput of interruptive requests. Put another way, it would be the number of interruptions your main product team would have to handle if you didn’t have a QRF team.

Performing categorization on these completed items can give key insights into the makeup and source of the various interruptions that would be experienced by your organization:

a high number of bugs could indicate quality issues

a high number of investigative asks could be a visibility issue

a high number of mundane data tasks could indicate a missing internal tool

Cycle Time and Lead Time can be used to provide predictive averages for new requests to requestors. If, for example, it took the last 100 items an average Lead Time of 3 days to complete, then a requestor can expect that, on average, their request will take 3 days.

Items Shifted Left represents the number of discrete workflows or categories of items that the QRF team has successfully prevented from ever occurring again. This represents initiative-gaining preventative work. Each category may represent dozens or hundreds of future interruptions that were prevented.

Interruptions Prevented is a metric that can be used to measure how ahead of the problem the QRF team is getting. One an item is shifted left (eg. through an internal tool) any future possible use of that “shift left” solution is an issue that engineering didn’t have to solve.

A QRF Success Story

I’ve successfully implemented this model at a few companies now.

One, which I’ll call “PayCo”, had a massive problem: over a dozen requests were coming in every single day, and only a couple of key engineers in the company knew how to solve them. They were busy working on other things, so those things didn’t get done, adding to an ever-growing backlog. Eventually, the embers would turn into a fire that required immediate attention, causing severe interruptions.

When I first joined, there was a massive backlog of tasks and asks. I knew this wasn’t sustainable, so I quickly spun up a QRF team.

It was initially a slog. Every problem and request we encountered was novel and discovering how to resolve it took time.

However, we explicitly and carefully documented the problems and solutions we encountered, creating step-by-step guides and even writing quick “fill-in-the-blank” scripts we could use in the future. From the work, we identified and documented solutions to over 40 categories of requests.

From these categories, we identified key patterns:

Certain departments had high levels of requests brought on by a lack of visibility

Some frequent requestors asked for information that we could easily provide in their existing tooling

Some people just access issues — they could easily perform the action had they had access to the right tool

We implemented a series of shift-left work and completely erased the intake of 25 of those categories of requests from ever reaching engineering by empowering the requestors to solve the problems themselves or by addressing the root cause of the issues.

We went from handling and resolving 10+ interruptive requests per day to receiving less than 3 a week in just two short quarters, and eventually, sunset the QRF team as the first-response and turned it into an overflow response for the other teams.

Implementation advice

In order for QRF to succeed, it requires a certain set of commitments from the organization.

QRF must own its own intake and prioritization.

This means that other teams can’t tell QRF what to do. It chooses based on its mission to prevent interruptions and its capabilities to do so.

QRF cannot have a roadmap or backlog.

The whole point of QRF is to be responsive, and it can’t be responsive if it has a backlog of commitments it must deliver on. The team should always be free to drop whatever it is doing to work on something else if it is desired.

QRF must have the authority to resolve issues.

It must be able to work with stakeholders and other departments directly to resolve issues, which might include process changes, interface tweaks, or the introduction of tooling. Any permission gating simply adds wait time and delays, which makes the team less responsive and interruptions more urgent.

QRF must be generalists with high initiative, adaptability, and attention to detail.

The team needs to be staffed with engineers who enjoy working on different things, diving into problems, working with stakeholders, and recording and tracking resolutions down with little to no support. Otherwise, it becomes difficult for them to affect change, gather information, and share larger solutions with the company.

The company must intake requests into a central location.

QRF works when it can easily identify requests that fit its operating parameters and can identify long-term request patterns. This can only be done if requests are articulated consistently and visibly.

In short — QRF can’t respond to requests it doesn’t know about.

If you don’t have a formal intake process, set one up!

Members of QRF must be thorough, clear documenters.

Part of QRF is discovering how to resolve an issue and making it so it only needs to be solved once — this often means writing down resolution steps in a way that can be reproduced by others across the company, or detailing requests and resolutions so that patterns can be uncovered for a larger preventative solution.

If you staff a QRF team with people who hate documentation, the team will end up solving the same problem over and over.

Avoid short-term engineer rotations.

There’s a certain amount of familiarity that is required to be effective in the QRF operational model that you just can’t build in a couple weeks. You need to be able to chase down threads, communicate with stakeholders, identify patterns to shift left. Switching an engineer off every couple of weeks prevents that momentum from building.

Set a Response SLA.

The whole point of QRF is providing responses in a timely fashion. Therefore, have the team commit to a response service level agreement.

Something like “we will respond to all requests within 48-hours” will help keep it from becoming an unpredictable black hole. Note that response doesn’t necessarily mean resolution — it just means that people will know whether it is going to be picked up by QRF or not.

Frequently Asked Questions

Isn’t that a bug team?

It’s easy to think “oh this is a bug team” — you couldn’t be farther from the truth.

Yes — it often starts out as a team that fixes a lot of bugs, but QRF is distinct in the way it prioritizes. Bug teams prioritize based on the criticality of a bug and go from there, and only work on bugs.

The QRF, on the other hand, prioritizes based on the level of interruptive-ness and inefficiency. They may work on items that aren’t bugs at all. Their job is to prevent interruptions, not fix bugs. This may mean letting some bugs occur and remain in the system to create a longer-term preventative solution for another interruption.

How do you get engineers motivated to work on these tiny items?

Autonomy and gratitude.

One key part of QRF is that it allows for infinite autonomy, which is a large part of the draw for many engineers. Engineers on the team essentially get to decide what to work on during standby, provided you fulfill the reaction SLAs.

Initially, there won’t be a lot of downtimes, but gaps eventually form between one urgent item and the next. It’s in these gaps that the engineer can multiply their impact.

Due to the nature of requests, the QRF is also a team where you interact directly with the people you help. Some engineers find it incredibly motivating to deploy a fix or a tool and have an opportunity to speak immediately with the people who benefited the most from it. For all of the talk of customer collaboration in many product development teams, far too many continue to silo their engineers from their user-base, which makes opportunities like this an exception, not the norm.

Ultimately though, the QRF is not for everyone. If the engineer wants to just head down and code, don’t put them on a QRF team.

Should the QRF do Scrum?

No — Scrum’s prioritization tempo can be too long. The QRF may reprioritize daily, even in some cases several times a day, depending on the fires. That’s what makes it powerful — it’s a commitment to allow for that. Scrum does the opposite — it creates a near-immutable contract that specifies that reprioritization should (ideally) only occur at the end of a sprint.

It’s recommended that QRF does a pull-based execution model such as Kanban. Kanban works well because it helps limit work-in-progress, reduces batch sizes, makes work visible, and allows for swarming on blockers.

What happens if QRF runs out of stuff to do?

They work on preventative, shift-left work, or other multiplier items — it is really up to the discretion of the members of that team. The only criteria are that they keep their queue as clear as possible by responding to and resolving items in a timely fashion.

This means not chewing off massive, blocking multi-month projects and ensuring things they deliver are done iteratively and incrementally, in a way that can be dropped or interrupted at any time.

If the unlikely scenario that QRF truly does run out of interruptions to handle, it means they’ve done their job! It’s a smooth transition from there to become an internal team working on supporting efforts, a developer UX team, or be folded into another team altogether.

Isn’t this just adding a capacity commitment with extra steps?

If you look at it purely from the perspective of engineering capacity — then, yes. However, that’s an over-simplified comparison — you won’t get the same results if you were to take that same capacity and put it on a normal product team.

That’s because a key component of the QRF is that it operates completely differently than how other engineering teams in your company might operate. The team’s charter on prevention helps reduce incoming interruptions in the long-term a lot better than a partial-attention model might. The motivator of infinite autonomy helps keep engineers working in the model motivated and retained.

How many engineers do you need on the QRF team?

That’s up to you — the model can work with just a single engineer for a tiny team, or you can even have a team of several engineers. The important part is examining your rate of interruptive intake and making sure the QRF is staffed appropriately to prevent a significant number of those interruptions.

If it gets to the point your team needs to have a QRF larger than the Main Effort team, that’s highly indicative of much larger, upstream, possibly cross-functional organizational issues that need to be shifted left, such as consistent poor requirements, technical quality, or prioritization discipline.

Context matters

The QRF model can be highly effective but remember: there is no silver bullet that works in every scenario. Examine your context and situation.

I’ve found great success with this model in environments where:

Engineering is frequently interrupted in high-urgency environments

Complexity is such that the QRF can quickly onboard into areas

Prioritization frameworks place low value on operational asks

There is limited capacity relative to the work

The interruptions are incrementally valuable, or must actually be done

This model likely won’t work or be effective in environments where:

the interruptions are truly not important

the interruptions frequently turn into meaningful strategic pivots

solutions require highly specialized knowledge or expertise

enough capacity exists where interruptions can be absorbed by the organization as a whole

a mature prioritization process is already in use that factors in operational needs as well as innovation

Context matters. Ultimately, a blog post on the internet can’t fix your problems for you — at best it can give you a mental model that you can apply and possibly mold after evaluating your own context and needs. It’s quite possible a QRF model will solve your problem, but the opposite can be true as well: you’ll know best.

That’s it. If you’ve ever implemented a QRF or similar model and saw success (or failure), feel free to leave a comment!